What Do We Mean by “Fluency” in Math? A Look Inside 2nd Grade

Last week, our K–8 math teachers spent time in professional learning with our wonderful math consultant, Karen Schweitzer, digging into research on math fact fluency, particularly the work of Jennifer Bay-Williams. While “fluency” is a word that appears frequently in standards and testing, our conversations pushed us to ask a deeper question: What does fluency actually look like in a classroom where students are thinking, reasoning, and growing as mathematicians?

Traditionally, math fact fluency has been equated with speed i.e. how fast a student can recall an answer under pressure. Research tells a very different story. Bay-Williams defines fluency as the ability to work accurately, efficiently, flexibly, and with appropriate strategies. Speed may be an outcome of fluency, but it is not the starting point and it is certainly not the goal.

One of the most powerful ideas we explored is that fluency develops in three phases:

Counting (using objects, fingers, or mental counting)

Deriving (using known facts and strategies to figure out unknown ones)

Mastery (efficient recall or quick strategy use)

In our PD, we honed in on the deriving phase because this is where the real mathematical thinking happens, and where so much of our 2nd-grade work lives.

In a deriving classroom, students are constantly using what they already know to solve problems they don’t yet “just know.” A child might say, “I don’t know 7 + 5 right away, but I know that 7 is 5 and 2. So I can do 5 + 5 = 10, and then add 2 more to get 12.” This is not a workaround; it’s deep number sense. The student is decomposing numbers, making tens, and reasoning flexibly.

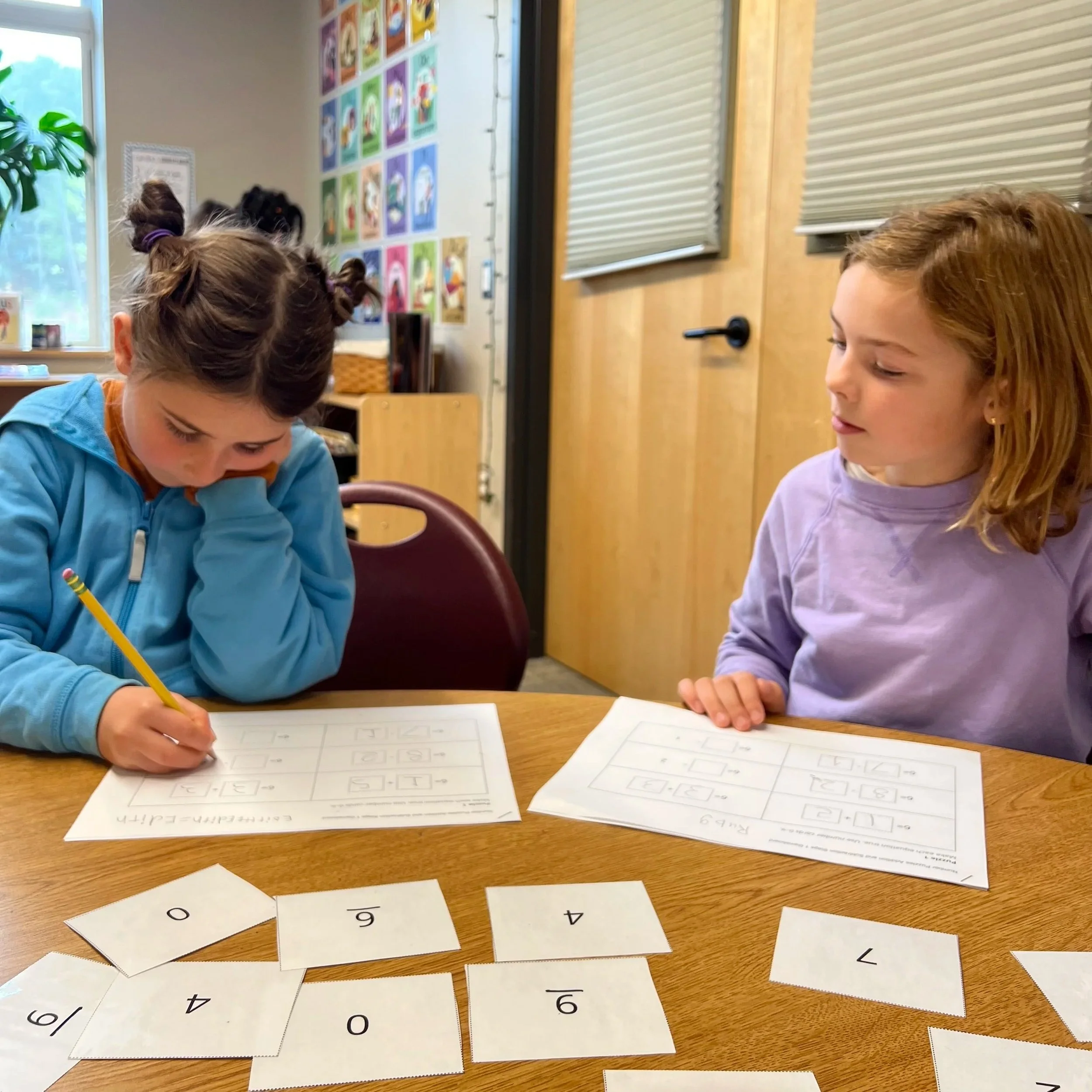

This way of thinking shows up in our curriculum, Illustrative Mathematics, which prioritizes understanding number relationships over memorization. When students work with number lines, ten-frames, and story problems, they are building the foundation that allows them to derive facts. Activities that ask students to explain their thinking, compare strategies with classmates, or choose among multiple solution paths all strengthen this phase of learning.

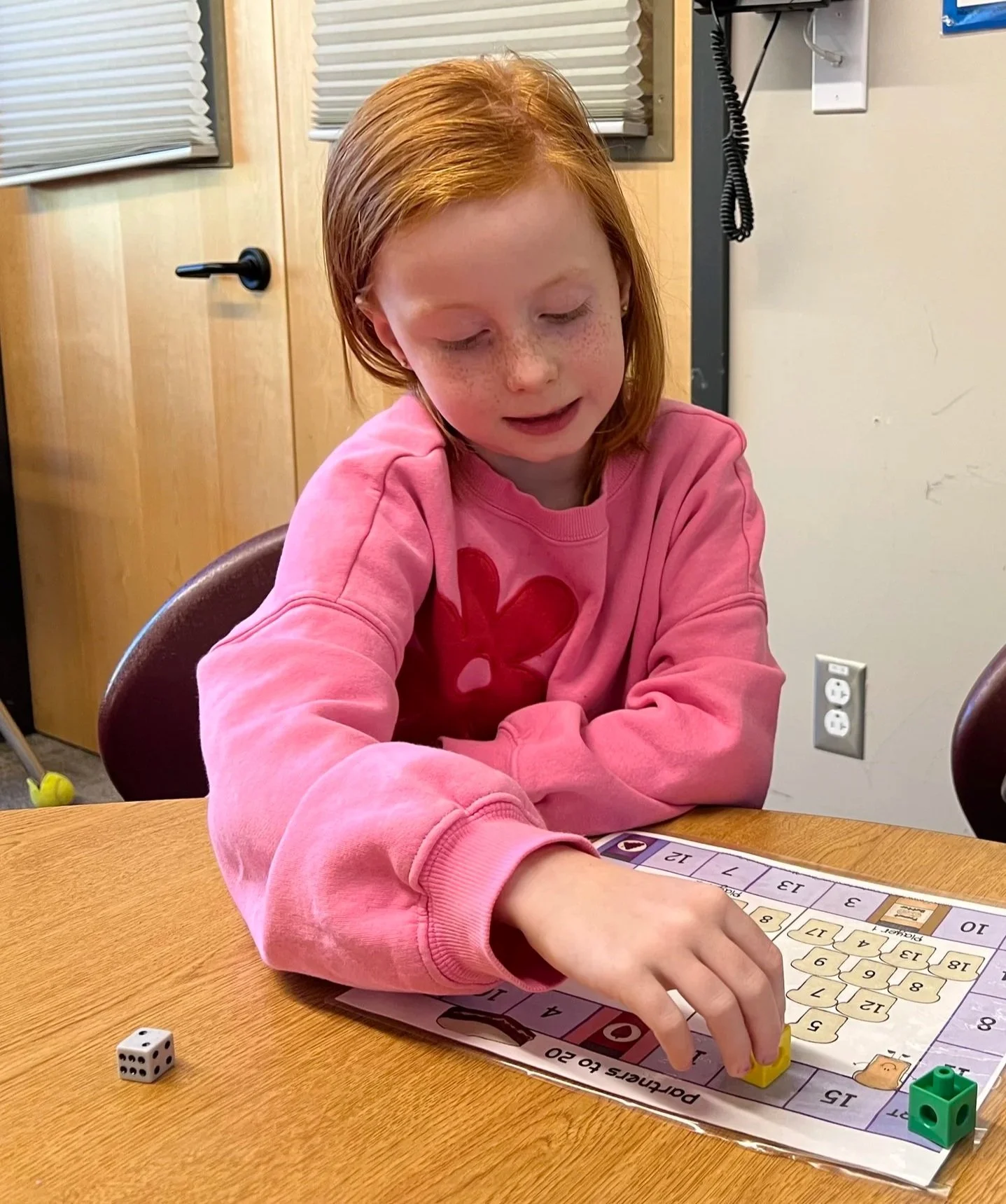

Fluency practice in 2nd grade, therefore, doesn’t look like rows of isolated problems on a timed worksheet. Instead, it often looks like games, conversation, and risk-taking. We play games like PB&J Partners to 20, where students search for combinations that make 20 and talk aloud about how they know. In How Close to 50?, students estimate, adjust, and refine their thinking as they add strategically. These games are fun but more importantly, they invite students to reason, adapt strategies, and learn from one another.

Games also give teachers a far richer window into student understanding than a timed test ever could. As students play, we listen: Which strategies are they choosing? Are they relying on counting, or are they deriving from known facts? Can they explain their thinking? This kind of formative assessment allows us to support students precisely where they are without the anxiety and false signals that often come with speed-based testing.

Perhaps most importantly, this approach protects something precious: students’ mathematical confidence. Research shows that timed testing can increase math anxiety, even in young children, and can disproportionately impact students who actually use more sophisticated strategies. In contrast, classrooms that emphasize strategy and discussion, help students see themselves as capable thinkers. They learn that not knowing right away is not a failure, it’s an invitation to think.

In 2nd grade, when students spend time in the deriving phase, they are not slowing down learning; they are deepening it. They are building flexible, connected knowledge that supports future work with larger numbers, multiplication, division, and algebraic thinking. This is how we prepare students not just to get answers but to understand math.